History and Mission

The objectives and purposes of the Association are: to improve, benefit and protect the well-being of the legal profession and its members; to enhance the professional skills of its members; to encourage professional and citizenship responsibilities among the Membership; to encourage spiritual and moral values; to advance the science of jurisprudence and the administration of justice; to improve the standards of legal education; and, to encourage legal research and excellence consistent with the philosophy of Houstonian Jurisprudence.

Jurisprudence, Benefit, Enhancement, And Protection

A Rolling History Of The Washington Bar Association

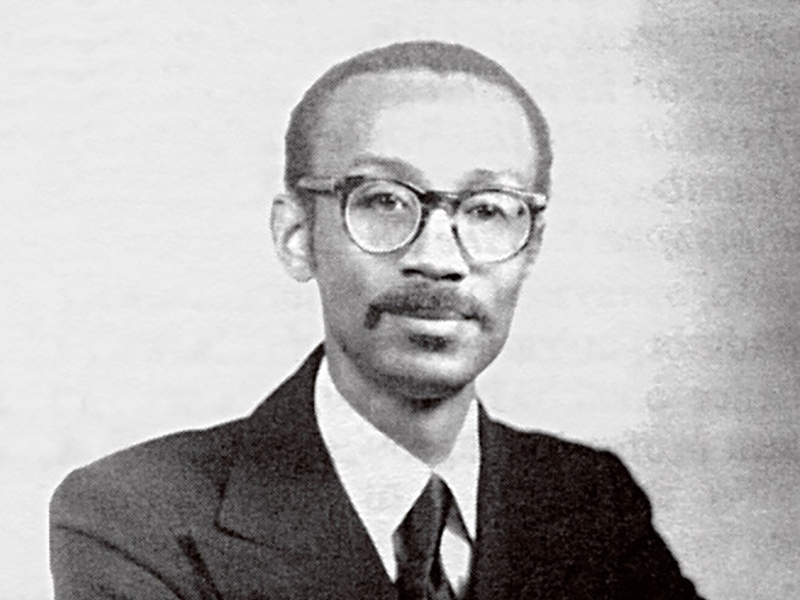

This document builds on “Jurisprudence, Benefit, Enhancement and Protection: the Washington Bar Association Turns Seventy,” authored by J. Clay Smith, Jr., while Professor of Law, Howard University School of Law for Law Day 1995. With Professor Smith’s permission, we have used it as the basis for a rolling history of the Washington Bar Association and have added significant events that have taken place since the WBA’s Seventieth Anniversary. We thank Professor Smith, the twenty-eighth President of the Washington Bar Association, for his contributions to this history.

This document builds on “Jurisprudence, Benefit, Enhancement and Protection: the Washington Bar Association Turns Seventy,” authored by J. Clay Smith, Jr., while Professor of Law, Howard University School of Law for Law Day 1995. With Professor Smith’s permission, we have used it as the basis for a rolling history of the Washington Bar Association and have added significant events that have taken place since the WBA’s Seventieth Anniversary. We thank Professor Smith, the twenty-eighth President of the Washington Bar Association, for his contributions to this history.

In 1916, before a seriously divided people, Democrats and Republicans fought over the issue of foreign policy to win the White House. President Woodrow Wilson was contending for a second term in the White House and faced a formidable challenge by his Republican opponent, Charles Evans Hughes. Justice Hughes resigned from his seat on the U.S. Supreme Court to make the run for the presidency. Europe was ravaged by war and the U.S. was about to enter World War I. Black lawyers in the District of Columbia, some of whom would fight in “the War to end all wars,” were themselves at war in the District of Columbia, fighting against unjust Jim Crow laws and other vestiges of slavery and overt racism.

The Colored Bar Association

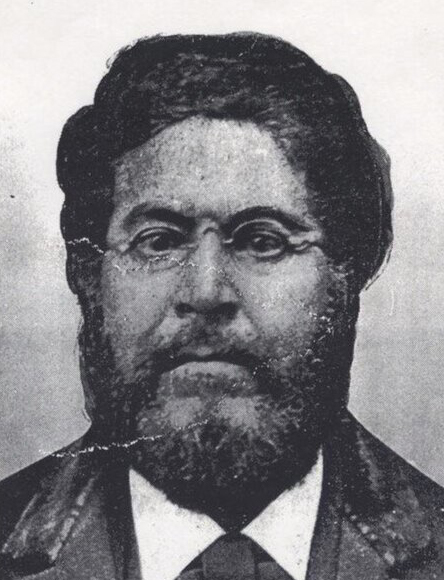

The experience of the black lawyer in the District of Columbia dates back to 1869, the year that George Boyer Vashon was admitted to the bar of the District of Columbia. His admission, followed by a small, but extremely competent number of black men and women, was the genesis of black lawyers’ initial discussions on the formation of a “colored bar association” in the District of Columbia.

In 1916, a small group of black lawyers formed the first loosely-knit bar group in the District of Columbia for their “mutual benefit and protection.” They recognized the need to form a group in order to survive in a profession dominated by a white legal fraternity that was inhospitable to them, and a white judicial system that could impede their improvement as lawyers. Barred from membership in the Bar Association of the District of Columbia (“BADC”) (founded on May 23, 1871), they formed the Colored Bar Association, under the leadership of William Lepre Houston, Laudros Meledez King, Emanuel D. Molyneaux, and others, thus laying the foundation for what would later be the Washington Bar Association.

The Washington Bar Association Founded

In 1925, the Washington Bar Association (“WBA”) was one of several black bar groups formed across the nation, as the National Bar Association (“NBA”) was being formed simultaneously. The purposes of the WBA and the NBA were similar to the aims of other states’ black bar groups that had formed prior to 1925. The similarities concerned advancement of jurisprudence, self benefit, group enhancement in a racially exclusive society and judicial system, and group protection.

The opportunity for success as a black bar group in the District of Columbia was significant because of the presence of Howard University School of Law, the John Mercer Langston Law School (a Department of the Frelinghuysen University), and the Robert H. Terrell Law School. The graduates of these predominantly black law schools joined the WBA. The presence of a black bar group protected laymen who, through the WBA, could complain about inequitable treatment in the public school system and employment discrimination in the local government and in the federal government. The presence of a black bar group also made it possible for the black community and black lawyers to complain to the local courts regarding police brutality against black citizens and the appointment of white judges, who were the political cronies of members of Congress, and to advocate for the appointment of black judges on the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, later known as the Municipal Court. This court today is the Superior Court for the District of Columbia.

The history of the WBA is rich, but largely untold. Some of the WBA’s most significant achievements and triumphs necessarily remain undisclosed, due to the sensitivity associated with national and local politics. The WBA’s history has been marked by its refusal to be silent in the face of adversity. Hence, it has elected strong men and women to lead the membership. The presidents of the WBA, some more courageous than others, have made inestimable sacrifices by taking stands against racial injustices facing the citizens of the District of Columbia, including the mistreatment of black citizens by the prosecuting arms of both the Office of the Corporation Counsel and the U.S. Attorneys Office. We salute and give special recognition to the current and past leaders of the WBA, and to its Founders: Ulysses Simpson Games, George E.C. Hayes, Charles Hamilton Houston, Isaiah Lisemby, Louis Rothschild Mehlinger, Charles E. Robinson, and J. Franklin Wilson.

Agitation and Persuasion

The membership of the WBA also, with much sacrifice, has given much to keep the WBA relevant and committed to its original objects of jurisprudence, benefit, enhancement, and protection. Individual members of the WBA have confronted and challenged the system when it trammelled the sacred principle and essential elements of justice and fair play.

A few examples are in order. In 1939, the Bar Association of the District of Columbia housed a library in the U.S. District Court building — a library that blacks could not use because they were not allowed to hold membership in the association because they were not white. A library in the courthouse provided white lawyers with a convenience that gave them a significant edge in trying cases. During court recesses, or at critical moments during a trial, white lawyers could run to the library in the courthouse to find precedents to support a point of law; black lawyers could not. Huver I. Brown, a member of the WBA, threatened to sue the Bar Association of the District of Columbia and sought the assistance of the WBA, which supported his claim. Word that the WBA and Brown also might join in the suit, as necessary parties, Harlan Fiske Stone, the Chief Justice of the United States and Robert H. Jackson, the U.S. Attorney General (the official joint landlords of the courthouse) caused quite a stir: the highest ranking U.S. judge and the nation’s highest legal officer were about to be sued in a matter involving racism against black lawyers.

The matter ultimately was settled. The U.S. Attorney General ordered the BADC to either allow black lawyers to use the library or to move out of the courthouse. The BADC then allowed black lawyers use of the library, for a service fee, but continued to bar them from membership. This matter also benefitted white women, who also were excluded from the same bar association. Brown’s action directly influenced the BADC to drop its male-only membership requirement, thus allowing white women to use the courthouse library. Black lawyers continued to be excluded from membership in BADC for more than twenty years. See J. CLAY SMITH, JR., EMANCIPATION: THE MAKING OF THE BLACK LAWYER, 1844-1944, at 578 (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993); Goshorn v. Bar Association of the District of Columbia, 152 F. Supp. 300 (D.D.C. 1957) (court refuses to strike white-only by-law provision.)

In other matters, in 1951, the WBA’s chairman of its Public Relations Committee, Charles Sumner Brown, argued that the public interest was ill-served without public-supported payment of lawyers who handled the cases of indigents. The WBA and Brown urged the support of S. 1210, a Bill “to provide the appointment and compensation of counsel to impoverished defendants in criminal cases in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.” In 1965, Charles Sumner Brown, in a letter to the Washington Post, complained that the method by which our bench is chosen leaves a lot to be desired. Brown inferred that the local judges and those appointed in the federal D.C. courts were largely incompetent in the field of criminal law. In 1961, during the deanship of Spottswood William Robinson III, the WBA helped to facilitate the placement of the Legal Aid Society at the Howard University School of Law to provide legal assistance to the poor in civil cases.

Women and the Washington Bar Association

Black women have played an important role in the development of the Washington Bar Association that reaches back to its first years. Ollie May Cooper and Isadora Augusta Jackson Letcher, were active members of the WBA. Both served as officers at one time or another. They nurtured and inspired the next generation of women lawyers in the WBA, one of whom is Wilhelmina Jackson Rolark, who, in the 1960s, was corresponding secretary. However, it was not until 1973 that a woman was elected president. Ruth Hankins Nesbitt, who had been a loyal member of the WBA for years, was elected to the office of president, but not without dissent. She served ably, and opened up opportunities for other women to head the WBA, to ascend to the bench, to head governmental posts, and to be hired in key positions in the private sector. Since then, the men and women of the WBA have supported and elected female leadership. As a result, to date, the WBA has had four women presidents – Ruth Hankins Nesbitt (1973-1975), Belva Newsome (1991-1993), Kim M. Keenan (2001-2003) and Felicia L. Chambers (2003-2005). Ms. Keenan is the first woman WBA President to become President of the National Bar Association, of which the WBA is an affiliate chapter.

Contemporary Challenges

The past often is the best teacher for the present and the future. The record demonstrates that many of the same challenges facing the black lawyer and the WBA that existed in yesteryear remained during more recent times. There has been much progress since 1916 and 1925. However, the record demonstrates that recent presidents and senior ex-presidents of the WBA continued to confront those who would deny the upward mobility of black lawyers, and the elevation of black women lawyers. Ex-presidents William S. Thompson (1954-1956), John McDaniels, Jr. (1972-1974), Nathaniel Speights (1986-1988), John A. Turner, Jr. (1984-1986), Iverson O. Mitchell, III (1982-1984), Belva Newsome (1991-1993), and Keith Watters (1988-1990), to name a few, appeared in the press on issues involving limitations and the black lawyer.

Under the Presidency of Michael M. Hicks (1993-1995), the WBA continued to be a force in the general welfare of the District of Columbia, pledging that the local and federal courts, the administrative staffs of the courts in this circuit, the Office of the Corporation Counsel, and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia were competently staffed and occupied by people of color, women, and fair-minded personnel who were in touch with all of the citizens of the District of Columbia.

The WBA In The Past Decade (2000-2010)

Despite the historical challenges the WBA faced, it has continued to grow and develop and to provide a beacon for African American lawyers in this City. Just a few highlights of the past decade will demonstrate that the WBA is a formidable force in the legal community that consistently builds on the principles established by its founder Charles Hamilton Houston.

Being instrumental in the creation of the Young Lawyers Division, Donald A. Thigpen (1999-2001), with the aid of Board Member A. Gilbert Douglass, formed the WBA’s Judicial Council Division in 2000. The Judicial Council Division provides a critical forum through which judicial officers in the District of Columbia can provide programs and activities for the community. Most notably, the Judicial Council Division puts on an Annual Spring Symposium on timely topics, which is open to the public and has instituted a Summer Intern Program that provides judicial internships for law students from all over the country. At Law Day 1999, the Washington Bar awarded the Charles Hamilton Houston Medallion of Merit to the Honorable Norma Holloway Johnson, the first African American female Chief Judge of the U. S. District Court for the District of Columbia. During Mr. Thigpen’s tenure, Chief Justice of the United States William H. Rehnquist — for the first and only time — brought greetings to our organization at the Ollie Mae Cooper Ceremony in 2000. Mr. Thigpen’s tenure as President was further distinguished by the conferring in 2001 of the Houston Medallion on Professor Charles Ogletree, the Jesse Climenko Professor of Law and Vice Dean for Clinical Programs at Harvard Law School and the Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the University of the District of Columbia.

As the fortieth President of the Washington Bar Association, and the third woman President in the history of the organization, Kim M. Keenan (2001-2003) was determined to expand the WBA’s ability to support the pipeline of future lawyers. To that end, she co-founded, with Vice-President Patricia Rosier, the Washington Bar Association Legal Fund, Inc., a 501(c)(3) organization. The Legal Fund has provided scholarships to law students throughout the city as well as scholarships and financial support to students at the Thurgood Marshall Academy in Southeast Washington. Since its inception, the Legal Fund has sponsored students to attend the award-winning Crump Law Camp sponsored by the National Bar Association and has worked cooperatively with the Washington Bar Association in implementing its agenda, including the Annual Law Day Dinner and the Brown v. Board of Education Celebration at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. True to the stellar legacy she began in the WBA, in June 2009, Kim was elected as the president of the DC Bar.

Felicia L. Chambers (2003-2005) continued the trend of adding riches to the depth of the Washington Bar Association. She instituted the Career Fair for Law Students, modeled after a program held by the Department of Justice Association of Black Attorneys, which provides law students practical career advice and career opportunities in all sectors of the legal community. Under her leadership, the WBA answered the call of then NBA President Kim M. Keenan, to be an active force in the 2004 Election Protection Effort. In partnership with the WBA Legal Fund, the WBA celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education in two parts – the Annual Law Day Dinner, chaired by Vice-President and Chairman of the Board Kevin D. Judd, during which the organizations awarded the Charles Hamilton Houston Medallion of Merit to the Honorable William Coleman, one of the lawyers who worked on Brown, and a panel discussion and festive program, inter alia, celebrating Brown at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, an event chaired by Robert Bell. She has also determined that the WBA Legal Clinic, which educates community members about legal problems most likely to affect them, will again be a regular part of the WBA Calendar as it was in the WBA’s earlier years. That program, chaired by Vice-President Iris McCollum Green, was last held during Ms. Keenan’s Presidency.

During Kevin D. Judd’s Presidency (2005-2007), the WBA received the Outstanding Affiliate of the Year Award by the NBA. His progressive leadership style and service enabled the WBA to reap many accomplishments in various areas, such as operations, membership services and community activism. All of these accomplishments have enhanced the WBA’s image within the Washington, D.C. area’s professional community, as well as the community at large. For example, the WBA’s by-laws were revised to streamline the WBA’s ability to conduct business to better accomplish the Bar’s mission in uplifting the legal profession and the community. One of the major creations from the passage of the revised by-laws was a Law Student class of membership. This change enabled the WBA to establish a direct pipeline for law school graduates to join the WBA’s membership after law school, thus keeping the WBA vibrant as it move further into the 21st century. In addition, during his administration, Past President Judd charged both the Judicial Council Division and the Young Lawyers Division to develop a myriad of programs interspersed among the Bar’s signature programs. As a result, both divisions met the challenge and developed exceptional seminars, symposiums, workshops and networking receptions for our membership and law students. Lastly, Past-President Judd implemented a comprehensive and rigorous procedure for recommending prospective nominees to the Judiciary through our Judicial Selection and Evaluation committee, which was chaired by Past President Kim Keenan. The committee now interviews and assesses the credentials of candidates who are up for judicial nomination before the WBA provide letters of recommendations to the District of Columbia Judicial Nomination Commission.

The Washington Bar Association continued its leadership, growth and development into all aspects of the legal community in our nation’s capital during the Presidency of Robert L. Bell (2007-2008). Under the leadership of President Bell, the WBA established the WBA Law Student Division, with Crystal Queen, a student at Howard University School of Law, serving as the inaugural Chair. In addition, under Mr. Bell’s leadership, the WBA Book Club was established. Past WBA President Felicia Chambers served as the first Chair of the WBA Book Club. Further, in fulfilling one of his campaign promises, President Bell initiated the Inaugural Annual Conference of the Washington Bar Association. The theme of the WBA Inaugural Annual Conference was “Intergenerational Dialogue: The Role of the Black Lawyer of Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow.” The WBA Inaugural Annual Conference was held at the historic Charles Sumner School on Thursday, June 19, 2008 (JUNETEENTH). India Pinkney (WBA board member) served as the 2008 chair. The Inaugural Annual Conference was an all day event consisting of, among others, panel discussions from prominent law school deans and law professors; a panel discussion with judges from the local trial, appeals and federal courts; and panel discussions by prominent lawyers in trail blazing areas of the legal and business communities. The Annual Conference opened with a Presidential Showcase Seminar and ended with a WBA Book Club Meeting. Prominent local attorney Ted J. William, Esq., gave a book review and led a book club discussion. The Inaugural Annual Conference was held at the same site and day as the 2008 WBA Annual Meeting, which was followed by the Annual WBA Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony. Further, President Bell continued the WBA’s leadership role in service to the bench and legal profession by serving as Co-Chair of the JUST THE BEGINNING FOUNDATION (JTBF) 2008 Trailblazers Panel, during its Eighth Biennial Conference in Washington, D.C. WBA Past President, Kim Keenan, served as Moderator and Co-Chair of the JTBF 2008 Trailblazers Panel, which was held at Howard University School of Law. Before his tenure ended, President Bell appointed Rodney Pratt (Second Vice-President and former YLD Chair) as the first General Counsel for the Washington Bar Association.

On To The Future

In closing, much remains to be done in the days ahead to combat the country’s attitudes towards race and to remedy (to make whole) present and past racial discrimination. Political efforts to replace the historic victims of racial discrimination with non-historic victims cast ugly shadows on the progress of race relations. The WBA will continue to have a role to play to ensure that constitutional guarantees are not further diluted, civil rights laws are enforced, and that the District of Columbia is freed from bondage and can stand on its own feet. WBA must continue to attract mighty leaders and people willing to work to secure the association so that in the years to come members of WBA will be able to expand their knowledge of the science of jurisprudence, benefit from the collegiality incidental to membership, enhance the rights, dignity, and humanity of the citizens of the District of Columbia and be rooted in positions to protect powerless citizens from all unjust harm and disenfranchisement.